During this season of moody brooding, I remembered how much I missed you, dearest Friend and Reader, so I thought it was the perfect prompt for me to pay a brief visit to see how you’re doing. I hope that you’ve been coping well. It’s undoubtedly been a paranormal Twilight Zone for all of us, one way or another, and a sudden and abrupt halt on a path we didn’t expect. We’re only now shaking our heads and looking up around at the new landscape of our daily lives.

I’m grateful to say that I’m good, and our family has been blessed by a wonderful little girl—Ruby Vera—my first grandchild, who arrived a month early in February. Of course, she’s beautiful, healthy, brilliant, wonderous, and a very old soul despite being just eight months old. I’ve been able to spend time with her a couple of days each week—and our precious rendezvous are such sacred moments and such happy respites from the din of the outside world. Ruby V makes me delighted to be me, her Mamie.

But back to the supernatural veil that’s being parted, especially for those of us who have been secretly inhabiting private spheres of loss and longing, day in and day out, for longer than we can even remember. We live with ghosts, or rather, we choose to live with our night-shades, which doesn’t leave much room –physically, emotionally, and psychically--for us to grow, explore or discover what’s on the other side of our grief. For if there is a ghost, there is grief.

Believe it or not, I find a strange comfort in stories about women, houses, and ghosts. Some of the greatest ghost stories involve houses—think about Daphne du Maurier’s astonishing novel Rebecca published in 1938. And the great Cornwall estate is known as Manderley. “Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again.” It was an international best-seller and has never gone out of print. Thanks to Alfred Hitchcock’s Academy Award-winning 1940 film –a stunning gothic romantic noir starring Laurence Olivier and Joan Fontaine, Rebecca has become an iconic metaphor for becoming a woman. In her own life Daphne du Maurier’s Cornwall home, Menabilly, became a secret code for her life’s work which always seems inevitably bound by the extraordinary three-dimensional trinity of women, houses and, ghosts. Daphne du Maurier’s many ghostly lives were not deciphered until after her death.

My cherished All Hallows Eve solo seasonal indulgence has become a ritual of dipping into much-loved suspenseful short stories, as well as watching black and white obscure cinematic thrillers, especially English and Irish ghost stories. I cuddle on the bed with spiced hot apple cider, the cats, and a small bag of good chocolates. Pleasure is perfected if the ghost story includes a house that holds secrets. Every home tries to shelter the secrets of the woman who lived there once, in the same way, that the woman once upon a time loved the house. The American poet Louise Townsend Nicholl put it best:

I gave my love to the house forever

I will come till I cannot come, I said

And the house said I will know

The Anglo-Irish writer Elizabeth Bowen is a personal favorite for ghost stories, especially her goosebump short story Hand in Glove (1952). Bowen believed that the truly scary supernatural story “lies in their being just, just out of the true.” Just out of the frame of life, lingering, observing you. Haunting. Remembering.

Another perennial favorite Hallowe’en book is Alison Lurie's collection of 9 eerie tales in Women and Ghosts. I especially love the visitation to a woman who thinks she’s marrying Mr. Right by the ghost of his first wife. How many times do former wives try to warn their successors? How many times do we not listen? This is another dreadful way to become a shroud in your own near-life experience.

Now the spine-tingling dramatis personae of the American author Edith Wharton is revealed in between the lines of a long out-of-print collection of ghost stories just published by the New York Review of Books with her original preface: The Ghost Stories of Edith Wharton. Celebrated as one of the most astute and deft chroniclers of the New York upper classes during the 19th century’s Gilded Age of robber barons, which followed the Civil War, Wharton only published her first novel (The Valley of Decision 1902) when she was forty. Before then, she was an interior and landscape designer. Her famous novels were The House of Mirth(1905) and The Age of Innocence which won her the Pulitzer Prize in Literature in 1921, the first woman to do so. Still, the paranormal doesn’t immediately come to mind when one thinks of Wharton, as much as the corseted, closeted straight-laced, prim, and proper prose does. Still, when she put together a collection of her ghostly short stories written between 1902 to 1937, she let the figments of unfulfilled passion and desire out into the shivery night where they belonged.

The last three decades of Wharton’s life were lived as an American ex-pat residing in France with an apartment in Paris and a house that had been a 17th-century convent built on a hillside overlooking the Mediterranean called Hyéres in the south of France. Wharton was a complicated woman, as was Daphne du Maurier, Elizabeth Bowen, and us all, leading many secret lives that were only revealed after their deaths—and hence they lived with ghosts all their lives. But now, their ghosts can become sources of inspiration for those of us who will read between their lines.

Edith Wharton confides: “I have sometimes thought that a woman’s nature is like a great house full of rooms: there is the hall, through which everyone passes in going in and out; the drawing-room, where one receives formal visits; the sitting-room, where the members of the family come and go as they like; but beyond that far beyond, are the other rooms, the handles of whose doors perhaps are never turned; no one knows the way to them, no one knows whither they lead; and in the innermost room, the holy of holies, the soul sits alone and waits for a footstep that never comes.”

In her autobiography, A Backwards Glance, Wharton confesses: “Years ago I said to myself: “There’s no such thing as old age, there is only sorrow.”… I have learned with the passing of time that this, though true, is not the whole truth. The other producer of old age is habit: the deathly process of doing the same thing in the same way at the same hour day after day, first from carelessness, then from inclination, at last from cowardice or inertia. Luckily, the inconsequential life is not the only alternative; for caprice is as ruinous as routine. Habit is necessary; it is the habit of having habits, of turning a trail into a rut, that must be incessantly fought against if one is to remain alive.

“In spite of illness, in spite even of the arch-enemy sorrow, one can remain alive long past the usual date of disintegration if one is unafraid of change, insatiable in intellectual curiosity, interested in big things, and happy in small ways.”

Perhaps women adore ghost stories because we have such a difficult time letting go. Bring up the topic of ghosts at any dinner party, and most of the female guests will be able to contribute an anecdote of a sighting or a haunting, usually set in old houses.

But “objects have ghostly emanations, too that attach themselves to their solidity,” the writer Dominique Browning tells us in her marvelous book, Around the House and In the Garden: A Memoir of Heartbreak, Healing, and Home Improvement. “Things with drawers—chest, armoires, night tables, trunks—seem to be most populated pieces of furniture.”

I have had a difficult time leaving my beloved home Newton’s Chapel, in England. It has been twelve years since the severing, made even more acute because I stored my belonging in containers on both sides of the Atlantic for all this time, paying the equivalent of a mortgage to house boxes instead of myself.

The medical-intuitive (a spiritual diagnostician) Caroline Myss, a pioneer in the field of energy medicine and human consciousness, tells us that when we know we are supposed to move on or out of a situation that is stunting our soul’s growth, and we consciously refuse to do so because the unchartered terror of choice and change scares us, a celestial clock starts ticking. “If you’re getting directions, ‘Move on with your life, let go of something,’ then do it. Have the courage to do it. This is the way it is. When you let go of something, it’s sort of like a time warning that says,’ You have ten days left. After that, your angel’s going to do it.’ So, the desire to hold on is not going to stop the process of change…You know that’s true.”

I’ll never forget the moment I heard her tell me that while listening to her audiotape Spiritual Madness: The Necessity of Meeting God in Darkness. Isn’t that interesting? I thought…I wonder if she’s right. Ten days later, my life was lying in smithereens around my ankles, and I was shaking my head, terrified, stunned, and incredulous in the presence of passion and betrayal. When you hear, see, read, or intuit your authentic truth, pay attention. You can run, but you cannot hide, especially from your ghosts.

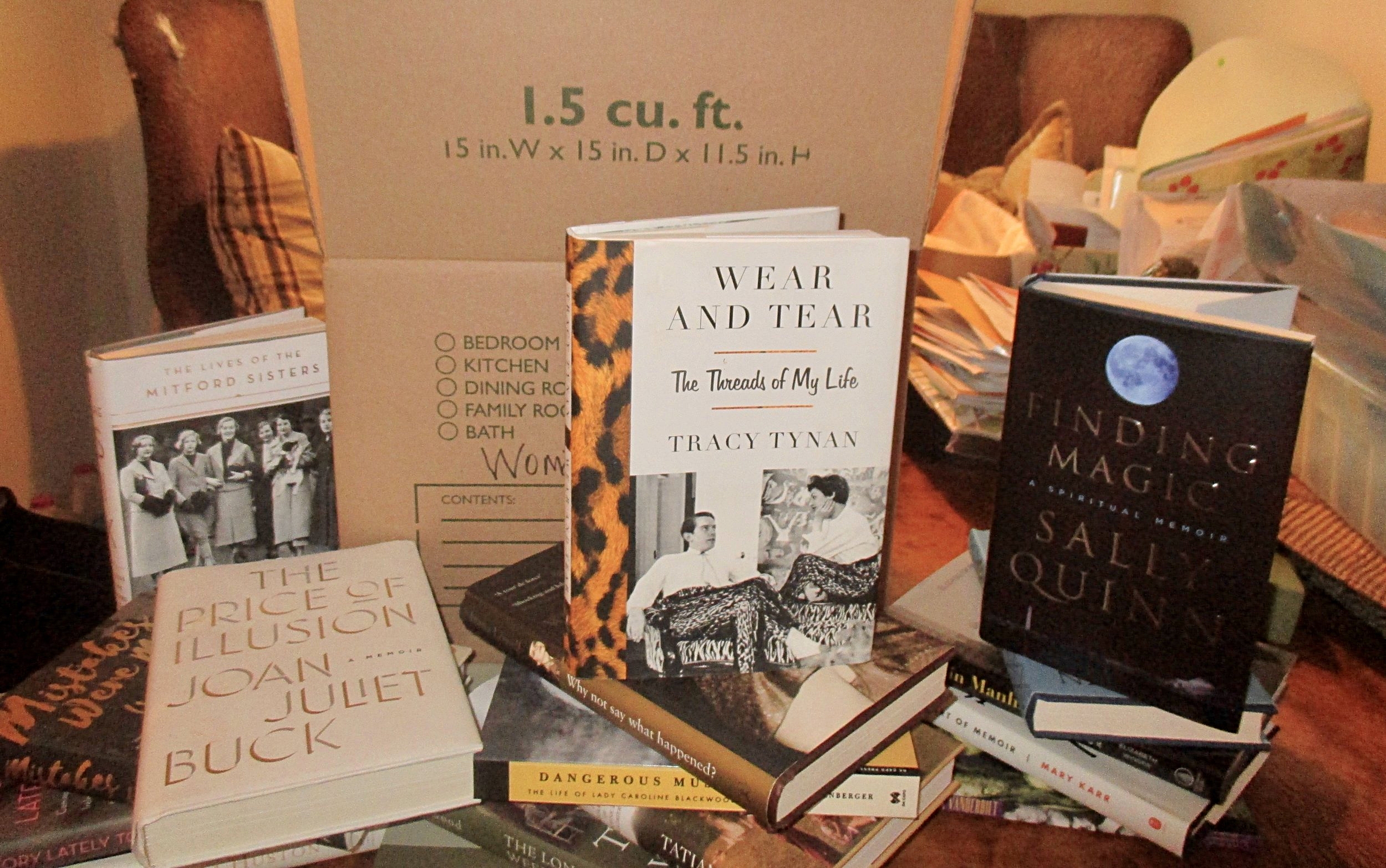

So as Halloween turns into the season of November’s All Souls Day and Thanksgiving, I’m beginning to sort through a one-bedroom apartment and two garages full to the brim of mysterious brown boxes. It’s the remainder of all I strived with every fiber of my being to hold on to—the remains of the days of my English dream—linens, rugs, paintings, personal objects, a few antiques, and probably more throw pillows than any sane woman should own, but that’s another story for another day.

I know that half of my collection will go to another auction. Still, this time I’m hoping that I don’t hover like a ghostly spirit wanting to share the item’s unique history but prevented from the Other Side, mixed in with the distress that something you found priceless is now somebody else’s bargain.

These boxes hold all the things I’ve loved, collected over a lifetime, and used to create a beautiful home for myself and my daughter; the antique beds and their William Morris canopies, the grandfather clock, the 17th century carved mirror that hung in the nave of Newton’s Chapel, the stunning sculpture of Sir Isaac Newton by the marvelous English sculptor Graeme Mitcheson; the Arts and Crafts chandelier and furniture designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh and created by the Glasgow Art School from his original drawings. I was such a lucky woman to be able to work with so many artists. I am so grateful for the blessing of living in such a beautiful home that cherished the past and nurtured our souls. No more than now, I suppose, when I have chosen to let go.

I never told you that gratitude had to be expressed with big smiles. I (hope) that the “thank you” offered in defeat, disillusionment, disappointment, and despair are the most treasured because they are priceless tokens of trust, especially when trusting Heaven is the last thing in the world you want to do. I hope there is another home I will be led to and will love, but I also know that I can’t keep looking back anymore if I want to find it. Nor can you. I finally understand the Biblical story of poor Lot’s wife, who was warned not to look back as angels were leading her family to safety—evacuating a cataclysmic disaster—as many of you have had to do in these last few calamitic years. But she did turn back to look one more time at all she was leaving and losing and was turned into a pillar of salt. The salt was from her tears.

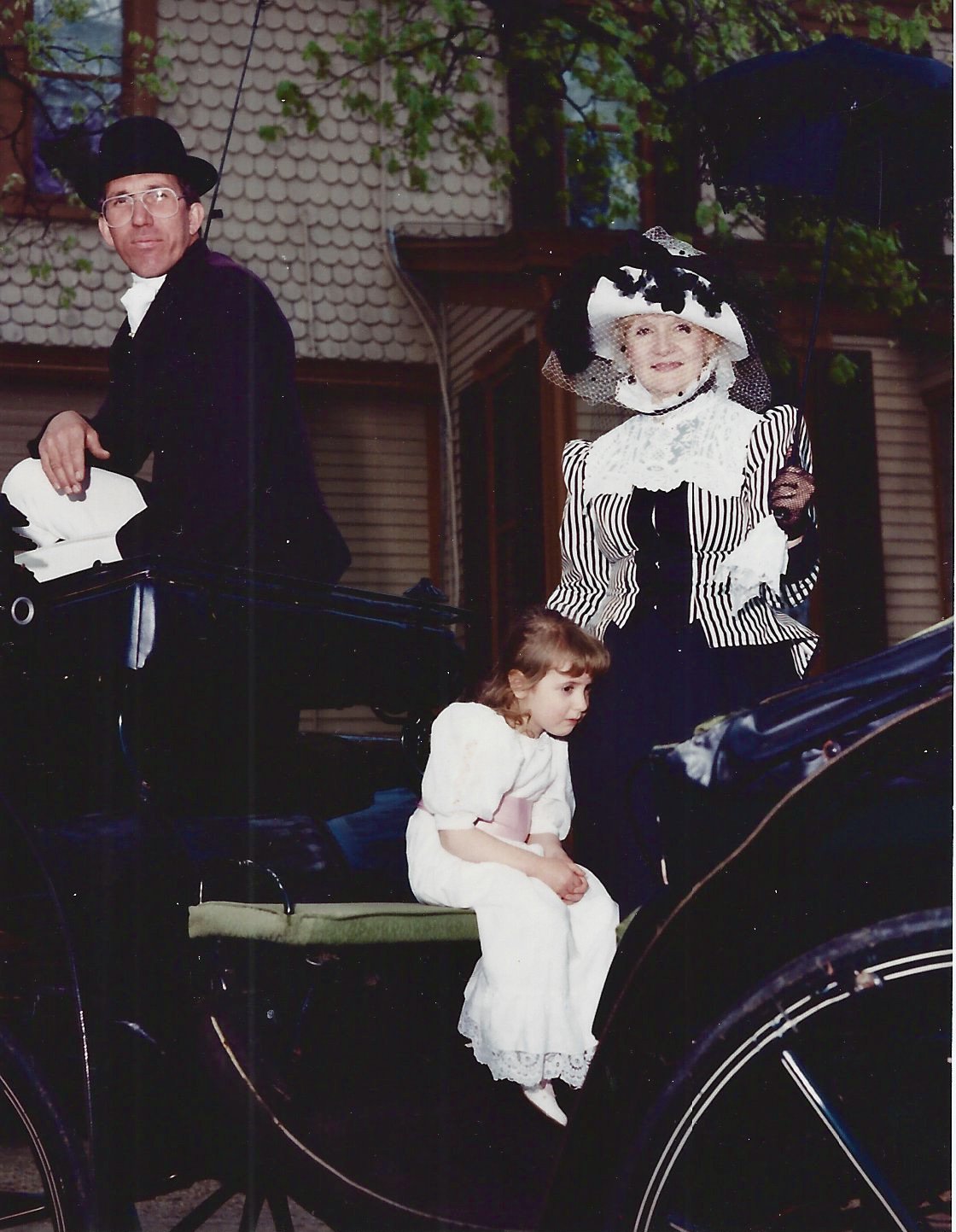

“Only in a house where one has learnt to be lonely does one have this solicitude for things,” Elizabeth Bowen confessed in her masterpiece The Death of the Heart (1938). One’s relation to them, the daily seeing or touching, begins to become love, and to lay one open to pain.” Bowen struggled her entire life to keep her family’s old Irish home Bowen’s Court; she had a nervous breakdown over unpaid bills in the 1950s. After she “recovered” she lectured and taught in the States to keep it going. Finally, she was forced to sell and then lived to see her beloved home torn down and razed to the ground. She spent the rest of her life living in hotels or with friends. I know I’m at a new threshold, and I pray to move through this change with as much grace and grit as Daphne du Maurier, Edith Wharton, and Elizabeth Bowen did in tweed suits, pearls, and heels. When I look at the courageous women who have gone before me—I call them my Swell Dames—they offer me a hand to help and guide me as I begin again. I feel such a deep connection with these women with a past because, as Bowen said, their ghosts are “just out of being true.”

So, if you have to let go, move on and begin again, you’ve come to the right friend, who’s learned that loving and losing are both sides of our ghost stories: the Here and After.

“I have tried to give away some of the things in my house that have ghosts; I think they would be better off somewhere else, and I want to be rid of certain memories,” Dominique Browning confesses, indeed for all of us. “…the armoire that was part of a marriage, the carpet that was part of a love affair, the photograph that was part of hope, the bedcovers that were part of too many sleepless nights. Begone.”

Offering a shoulder and one last loving, lingering look at whatever in your life is the long goodbye. May you be safe and sheltered in the embrace of Mother Plenty and guided by the Master Builder, and may you soon find your path to the hearth waiting in your heart. You have no idea how much I love you, and I am grateful for your calling me back into the world. I’ll keep the stories coming. May there be good chocolate in your future. Blessings on your courage and always, cherished friend and reader, dearest love.

XO SBB